Value Betting Fundamentals

This is the pillar article on Value Betting Fundamentals. Here we focus on what value is, why it beats "bankers" (a.k.a. "safe bets"), and provide with a practical guidance how to calculate and act on it (should you decided to do it in house).

Table of Contents

- What we mean by "value"

- Why the market can be wrong (and why value exists)

- Why betting "bankers" is often inferior

- The dice roll story: value vs "bankers"

- Variance, sample size and why "five losses" are not proof

- How to find and validate value — the pipeline (high level)

- Final thought — the mindset that wins

What we mean by “value”

First things first:

In symbols:

- Let be the decimal odds offered (e.g., 2.50).

- The bookmaker’s implied probability is .

- Let be your estimate of the true probability of the outcome.

A value bet exists if:

Expected profit per unit stake (EV) is:

Derivation (short): if you stake 1 unit, with probability you win units back (profit ), with probability you lose the 1 unit. So expected profit = which simplifies to .

Why the market can be wrong (and why value exists)

Reasons edges appear:

- Different objectives: bookies balance books; sharp money and public money interact with limits and hedging. That creates temporary mispricings.

- Behavioral biases: bettors overvalue favorites or certain narratives and push prices away from statistical reality.

- Information asymmetry: your model might capture nuance (player injuries, lineup hints, new coach styles, recent match context, weather forecasts, etc.) earlier than a market or you may simply draw better conclusions (automated or discretionary).

- Operational frictions: limits, regional markets, and slow-moving sportsbooks mean price discrepancies can persist.

Important: this is not a claim markets are easy to beat. It’s a claim that consistent, small edges — if real and executed properly — compound into long-term profit.

Why betting “bankers” is often inferior

“Bankers” are bets framed as safe winners — short odds, high implied probability. They feel low-risk but are often negative EV.

Example favorite:

- Suppose a market offers favorite at (implied probability, for simplicity assuming no vig, is ).

- Real probability is .

- Then expected value is:

You lose 10% of stake on average — a classic banker with no value.

Bankers create three problems:

- Tiny edge if any — even if your model is slightly positive, the bookmakers’ short prices leave little or negative EV.

- High rollover — to net meaningful returns you must stake more frequently (chasing value where it's not there) or take enormous volume; both increase operational risk.

- False comfort — because who doesn't like to be right, right? Yet it's so easy to mistake win frequency for profitability and underweight variance.

The dice roll story: value vs “bankers”

Simple stories stick. Imagine a fair six-sided die.

Scenario A: someone offers you 1.19x on the event “roll is 1–5” (i.e., win 19% profit if the die shows 1–5).

- Probability .

- Decimal odds .

- Expected profit per unit stake:

So you lose 0.83% of your stake on average per bet. No value here.

Scenario B: someone offers you 10x on the event “roll is 6” (i.e., win 10 times your stake if the die shows 6).

- Probability .

- Decimal odds .

- Expected profit per unit stake:

So you expect to gain 66.67% of your stake on average per bet. Enormous positive EV!

Which would you pick? Intuitively many people shy away from Option B, in exchange for the cosy feeling of being right most of the time. But smart bettor choses Option B. Option A is a classic banker, with short odds and negative EV, despite looking “safe”.

Variance, sample size and why “five losses” are not proof

Value betting relies on law of large numbers. A single series of losses or wins doesn’t tell you your edge is wrong or real — it may be a natural fluctuation. You must judge your system by long-run aggregated results.

Key relations:

- Strike rate (a.k.a. win rate) is how often you win; long-term profitability depends on both strike and payoff size.

- Variance increases with larger odds dispersion. Longshots have high variance (rare wins, big payoff); bankers have low variance but often little or negative EV.

- Sample size required to validate an edge scales inversely with square of edge. Small edges require many more bets to be statistically detectable. We’re talking hundreds and even thousands of bets here

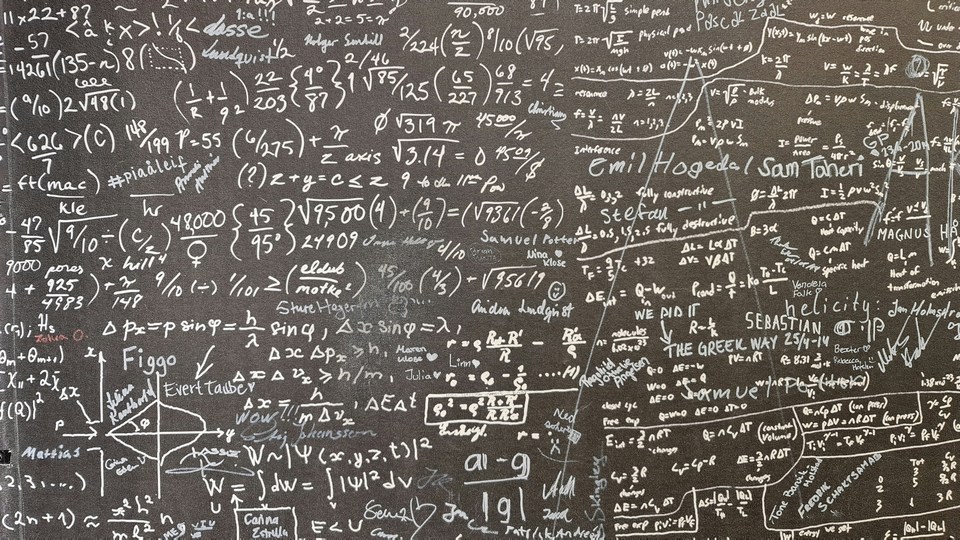

How to find and validate value — the pipeline (high level)

You want a reliable system — not random hunches. Here’s a compact, extendable pipeline you can build for yourself:

- Data ingestion

- Collect historical match data, lineups, weather, injuries, market prices (pre-match, exchange, in-play), and whatever data your model requires.

- Feature engineering

- Reliable features: xG metrics, shot locations, possession breakdown, recent opponent strength, rest days, travel, expected lineup strength, weather forecast, the list goes on and on…

- Modeling

- Use Poisson/negative binomial, Elo-type ratings, modern ML models, proprietary algorithms, whatever gives you the edge.

- Calibration

- Raw model outputs must be calibrated (Platt scaling, isotonic regression, or simple logistic calibration) so corresponds to true frequency.

- Backtesting & forward testing

- Out-of-sample testing, time-based splits, cross-validations and walk-forward testing to avoid look-ahead bias and overfitting.

- Edge detection

- Compare model to market implied (normalize for vig). Flag bets where exceeds a threshold.

- Monitoring & analytics

- Track EV, realized ROI, drawdown, and other important metrics

- Beware the common failure modes. Even if the math checks out, practical failure often comes from one of these:

- Models overfitting — probably the most common and most deadly fallacy - your model performs great on historical data but fails in real life scenario.

- Survivorship and lookahead bias — data leaks lead to overstated backtests.

- Calibration error — model probabilities are overconfident. You think you have value but your is inflated.

- Data mismatch — your historical data format differs from live conditions (different competition intensity, rule changes).

- Ignoring vig — always normalize implied probabilities before comparing to your .

Final thought — the mindset that wins

Value betting is a probabilistic business, not a spectator sport. The heroic tales you hear — one big score, one perfect ‘banker’ — are noise. Professionals think in expected value, stake proportion, variance and sample size. They accept short stretches of losses as the cost of doing business.

Three closing rules of thumb:

Good luck and see you inside!